Method calling itself

When a method calls itself, another entry is added to the top of the method stack.

Consider the following code:

1

2

3

public static void foo() {

foo();

}

This is the most basic recursive example, where the method foo calls itself, placing another instance on top of the stack.

Of course, since this process never terminates, the stack keeps growing infinitely. As you might imagine, there is a limit to the number of entries in the method stack and when this is reached, we get StackOverflowError.

Thus, our job is to ensure that methods don’t call themselves infinitely.

Consider the following code:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

public static void main(String[] args) {

int n = 4;

foo(n);

}

public static void foo(int n) {

System.out.println(n);

int m = n-1;

foo(m);

}

The output you will get before finally getting a StackOverflowError is:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

4

3

2

1

0

-1

-2

-3

-4

and on and on and on ...

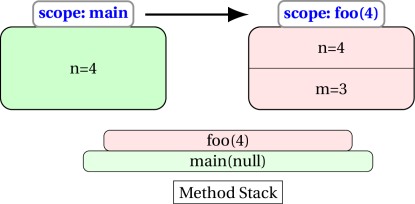

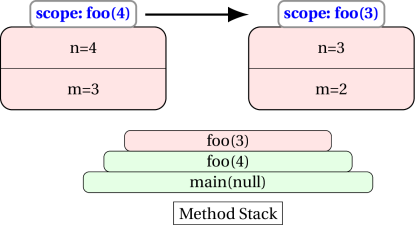

An illustration of memory transactions is given below

STEP 1: main calls foo(4)

STEP 2: foo(4) calls foo(3)

…and it repeats forever (ends with StackOverflowError)

End-case or terminal case is CRITICAL

It is critical that we have an end case of a terminal case.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

public static void foo(int n) {

if(n >= 1) {

System.out.println(n);

int m = n-1;

foo(m);

}

}

In the above modified method, we have enclosed the entire code in a conditional block. As soon as n drops below 1, it’s effectively an empty method body and it returns the control back to the caller.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

main(null) calls foo(4)

foo(4) displays 4 and calls foo(3)

foo(3) displays 3 and calls foo(2)

foo(2) displays 2 and calls foo(1)

foo(1) displays 1 and calls foo(0)

foo(0) does nothing and returns control to foo(1)

foo(1) returns control to foo(2)

foo(2) returns control to foo(3)

foo(3) returns control to foo(4)

foo(4) returns control to main(null)

The output you get is:

1

2

3

4

4

3

2

1